As a society, we are perpetually on a search for answers to the challenges we face in hard times. We want clarity and a path of right and wrong. We want justice and to feel like we helped fix something. We want to feel validated in our expressions of the political problems and exonerated in our own stressed out responses to the issues at hand. Answers are security. A cure for anxiety. A path forward. A perceived hope.

Or not.

Maybe answers are not what we should seek. Trying to find answers to political questions is a roadblock in taking the first steps towards neighborly love, that sacred virtue so many of us were taught as a child. Instead, the goal should be to get comfortable within the discomfort of difficult questions and to practice the kindness required to accept that we all think and talk in drafts. We wander our own minds on lost paths and dark alleyways, trying to navigate how to ask complicated questions in easy ways.

A few weeks ago, I visited a high school in New Jersey in honor of Holocaust Remembrance Day and ran two programs—one was a small-group workshop and the other an all-school assembly where 450 young faces stared back at me from a large, darkened hall. Outside it was the nicest day of the year so far; it felt like summer.

I began teaching my grandmother’s Holocaust survival story back before it was a book or a podcast, or any type of published name, shape or form. In the early 2010s, I pulled together threads of her story for the classroom when the principal of a Hebrew school I taught at gave me the green light to develop my own curriculums. It started with teaching a course on places around the world where Jews found refuge during the Holocaust. Then, at other schools, there were year-long curriculums focused on immigration and refugee rights. And classes about my grandmother’s experience learning about American racism upon arrival to this country in 1950. These days I focus more on the contagion of Nazism—how a society that seemed to be going so right, suddenly went so wrong.

I talk about how when my grandmother was growing up, in Czechoslovakia, her parents used to say, “What is happening in neighboring Germany could never happen here. Not in our democratic Czechoslovakia.” I’ve always told this part of the story, but now I sit with it longer and let my great grandparents' naïveté dramatically drift through the air.

As the world has changed, so has my family story. Not the facts or the bones of the narrative arc, but the meaning made and the memories I lean upon. And, more importantly for the shape of the story, as the world has changed, so have I—the narrator. My perspective has widened, my experiences have become hardened, and the questions I’m confronted with have deepened.

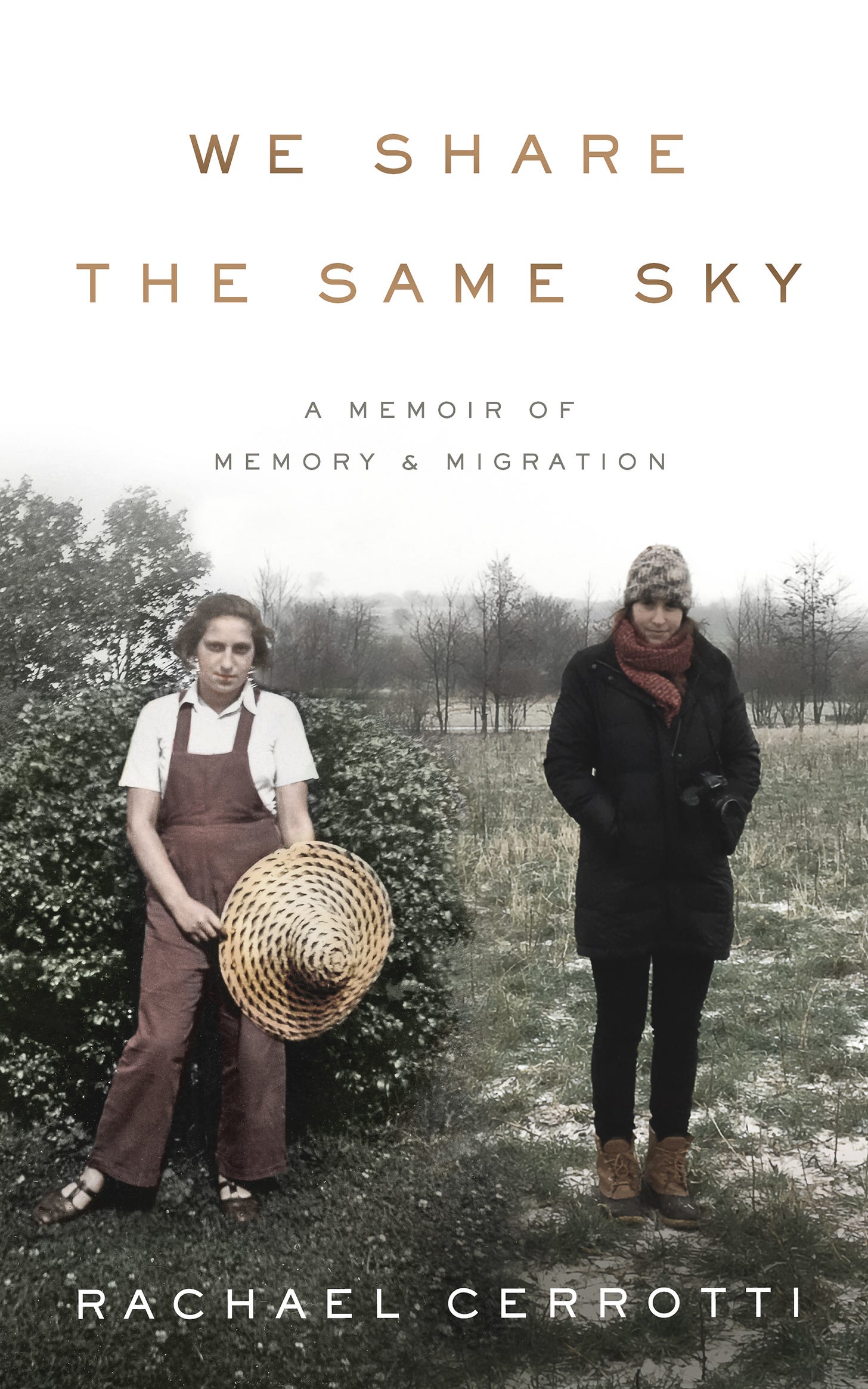

The workshop I taught at this school in New Jersey was for a group of students and teachers who formed a book club to read We Share The Same Sky, my memoir which tells the story of my decade-long journey to retrace my grandmother’s war story. And during that workshop, I got a question from a student that I could not answer (these are the best types of questions). A black student raised his hand and shared, “You know, for my whole life whenever we would learn about slavery in school, I always put myself in the place of the slave because that’s who I looked like. And I wonder if the white students put themselves in the place of the slave owners because that’s who they looked like?”

He then made a caveat that they certainly weren’t expected to before continuing. “But when I learn about the Holocaust, I don’t put myself in the position of the Jews, even though there is victimhood there, which I can understand. And I’m wondering if I’m supposed to? Are we supposed to be putting ourselves in the place of the people we identify with? And are we supposed to be putting ourselves in the place of the people we don’t identify with?”

He went on to share that he thinks that’s why so many people in this country are scared to teach about race, making the case that parents and teachers don’t want to traumatize a next generation with either identity: perpetrator or victim. They don’t want to make them feel like anything is their fault, their responsibility, or their burden to bear. And it’s hard, when you see someone you identify with, not to place yourself there.

This is a really good question and it hit everyone in the room, teachers and students alike. I find over and over again that high school students have a way of asking questions with a purity and a potency that adults lack.

I told him that I certainly have opinions and went on to share that my own deep dive into my family’s history has helped me better identify with other victim groups. It’s also helped me better identify with bystanders, as well as those who get caught up in the perpetrator role without having an evil bone in their body. I told him that I think a lot these days about the average Germans who were desperately trying to raise their children and keep food on the table in a time of war and upheaval. I can understand that many of them were not prejudiced and yet felt no option but to turn a blind eye when their persecuted neighbors, like my own great-grandparents, were deported from the community.

I told this student that I don’t have an answer. I don’t know if it’s healthy or helpful to identify so deeply with illuminated figures of the past. “At times I’ve certainly benefited by putting myself in my grandmother’s shoes,” I said. “But if I’m being honest, these days, it has felt more traumatizing than anything to think about the what ifs of who I am. My fear is mighty right now, as are my judgements. Which perhaps is useful, but just as likely is harmful.”

Wrestling with this student’s question was more important than coming up with an answer, and I told him that. “I wish the question didn’t feel so personal,” I added as we agreed as a group to let the question linger. We hung it in the air and let it surround us with its weight. Like the threads of our family histories, retold and reinterpreted, we agreed that the response should be malleable. Our histories are not enclosed in a glass case, and neither are our identities or the way the two relate. It all changes with time. As societies shift, our stories shift. As we progress or backslide, so do the meaning of our memories.

If you are an educator interested in bringing We Share The Same Sky into your classroom, you can learn more about the wide array of programming I offer for students as young as fourth grade through adult education on the project’s website: www.sharethesamesky.com/classroom

I love the way you handle these questions with so much grace and honesty and integrity. May the students --- and all of us! --- continue to learn and grow

Amazing story. I hear from my husband who is a non-Jew of German descent (and loves the Jewish culture) his empathy for the young German soldiers that were forced to fight in WWII.

I am reminded of the need for those soldiers to get drunk as a skunk at night to survive what they were mandated to do by their Nazi bosses. I see there is a need to empathize with both sides , as abhorrent as that may seem, as we see the young people of the world , empathizing with the plight of young Gaza children. The biggest existential threat we are all experiencing is winning the hearts and minds of the young generation. Sinwar wanted this war on video, he got it, to demonize Israel. I think including/framing current events into your presentation, is likely the most challenging, but clearly the most important part of your job. With all my respect and support, Jody