Back in 2009, I was a wide-eyed student at Hebrew University who knew little about history. I had only just started having the conversations with my grandmother that would become We Share The Same Sky, and I had only just arrived at an international school that would expand my community and my points of view.

The first friend I made at school was Sergiusz Scheller, who became a best friend, then my husband and, too soon after that, my-late husband. He was Polish, raised in a Catholic family, and much smarter than I when we met at the tender ages of 20 (me) and 21 (him). He exposed me to all sorts of things in life, like good techno music, how to roll a joint, and the political philosopher Hannah Arendt.

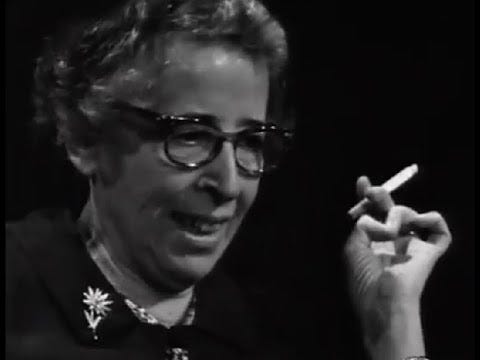

I remember him showing me an interview with Arendt on YouTube and being entranced watching this older woman chain smoking cigarettes in 1960s black and white footage. I doubt I understood any of her ideas at that time, and can say with certainty that if I did it wasn’t that which drew me in. I wasn’t ready for that type of intellectualism. Rather, it was the presence of this confident woman formulating ideas and using her words to push back against norms.

This introduction was before I knew anything about the Origins of Totalitarianism, The Human Condition, or the controversy she caused after reporting on the Eichmann Trial in 1961. It was before I knew about her education and the fact that she was well known for an affair she had with a professor who, when society asked him to, turned Nazi. And it was before I knew about her nearly two decades of statelessness or the details of her escape from an authoritarian and anti-semitic Germany. What I did know was that she was a German Jew who survived the war and then spent her entire life trying to understand it.

I fell in love with Hannah Arendt as an idea before I knew anything about her ideas.

Here is a short video of Hannah Arendt speaking about love in a political context.

As I grew into my twenties and began to entrench myself into the study of World War II, I learned more about her and began to think of her as a North Star of sorts. When I asked myself the hypothetical question, ”who would I want to be in a time of war,” she is the person I named.

Like her, I thought, I would leave the infected society and find refuge in order to survive. Like her, I thought, I would witness from afar and write.

I’ve carried this idea for a long time, but in recent years I’ve been confronted with what many of us face when we hit a certain point of adulthood: questions posed as hypotheticals don’t elicit the same answers as when they are up against the backdrop of reality.

It’s almost become a trope now for those of us who don’t subscribe to the Trump agenda to threaten to leave America. It’s an idea that I’ve heard, and myself have repeated, since 2016. I had been recently widowed when that election happened and was holding a grudge against my late-husband who had been European. In my gallows humor and with a whole bunch of love I often cursed him, as he was my passport out of this country.

At that juncture in my life—a 27-year-old nomadic journalist—I very likely would have left had I been able to. But instead I dealt with my discontent by further committing myself to studying my own grandmother’s Holocaust survival story. This involved immersing myself in books, including those written by Arendt. And due to current events, the sustained relevance of her ideas were glaring. Studying Arendt taught me to be thoughtful about the moral component of the narratives we shape around history. We must stare the evils of the past and present in the face and define them, and we certainly must oppose them. And at the same time, it’s just as critical to ask questions and spend time thinking in order to better understand them. Her comfort with the combustive type of inquiry required to create change inspired me.

It was her experience reporting on the Eichmann Trial that really left an impact. She alienated so much of her Jewish community in order to introduce a new vocabulary to how we talk about evil deeds. For example, the use of the word “banal” in her description “the banality of evil” infuriated so many Holocaust survivors as their experience, rightly so, was anything but banal. But she stood her ground. And I think that the wide lens she had, which was perhaps partly due to escaping Europe during the war (the lens I’ve always coveted), was what gave her the distance to question and not just feel. As a granddaughter who has spent my career inside my grandmother’s story, I resonate with that distance—albeit mine has been time, not proximity.

For years, we’ve been confronted by war seeping into all corners of our world. I do believe that when the history books look back on us, this time will be seen as part of World War III. Countries are sending bombs to one another, choosing to protect some people and not others, and interfering with elections. War is as advanced as our technology, and we have come a long way since the day the last world war ended in 1945.

Another short video of Hannah Arendt. This time she is speaking about what surprised her about Hitler’s rise to power.

And so now, in 2025, I come back to this question of: Who do I want to be in a time of war? The question, this time around, has certainly risen in stakes. It assaults me with urgency as each headline lands in my inbox. The fear I feel is against the backdrop of a life far more rooted than I’ve ever had before. I’m married again, with pets and a mortgage and a growing family. And I can’t so confidently say that I want to escape like Arendt did.

I certainly have moments of wanting to leave and sometimes that becomes a pursuit. But I also know that as our democracy gets dismantled, I find myself caring for this country more and more. I find myself wanting to stay and to peacefully persist and resist, in the ways I know how. I know I’m more able to use words than a sword, and more able to speak than fight. I know that I’m not powerful enough to convince our leadership to do better or to be better. But, maybe I can better my state of Maine, or my city, or at minimum simply be a good neighbor to those I know and those I don’t. The idea of witnessing from afar doesn’t feel as powerful anymore. The idea of contributing here does.

Three long years ago, at the start of the war in Ukraine, I was introduced to a woman named Alina Zievakova. Like Arendt, she is another badass woman who has used words to survive. Alina is a young actress living in Kyiv who, throughout the war, has used performance to help her fellow Ukrainians cope, heal and feel. We spoke on my podcast, Along The Seam, back in July 2022 and when talking about her choice to leave or stay in her country, she said this:

“Before the start of the full scale invasion, I always thought that if something dangerous will happen or something that, you know, makes sense to leave for survival purposes, I would be the first one to do that because I have friends and people who are willing to accommodate me [and] to help me in Europe and United States. But the moment it started the first day, I just had no doubt I was sure that I need to stay. There is no other place where I can be. It is my home. So therefore I need to defend it. I just couldn't bear the idea of running somewhere, of being away from it all."

Alina and I check in with each other every so often and she continues to be a source of comfort for me as history unfolds. I come back to her words often, checking in with myself about my own changing perspective on the world. I now feel some camaraderie in her acknowledgement that she too thought she might be among the first to flee. That honesty has a power in it that drives home one of the lessons I carry from Arendt: we must be free to change our minds and to ask different questions. One’s support for a theoretical idea may not remain as the idea shapes itself into reality.

And with that I’ve realized, that perhaps over all these years, I’ve been interpreting my own question all wrong. I’ve taken the question, who do I want to be in a time of war, and made the question about location. Do I want to be here or there? Wherever there is. But the question is about who, not where.

Following my own Jewish tradition, I find that to sit with this question is more important right now than to answer it. I genuinely don’t know what happens next, despite the blueprint of rescue and refuge I’ve inherited from my own family. And that not knowing has to be okay even if it makes me feel fear.

In the midst of my confusion, I’m finding that as I study the women of my past and present, the ones I only know from their books and the ones I know in person, I’m seeing so many North Stars. I hear them all whispering to me from their pages of history that the way to find answers is to think freely, feel deeply, question kindly and stay headstrong.

You can listen to Alina Zievakova on the Along The Seam podcast right here or on the website: www.alongtheseam.com